10 of the Greatest Japanese Movie Directors – From ultraviolent crime fests to lush animations, to ponderous explorations of the human condition, Japanese movies have long fascinated global audiences.

The following are 10 of the best Japanese movie directors whose masterpieces you must watch no matter your level of interest in Japanese cinema. If you’re watching any of their works before or during a Japanese holiday, know too that many will offer piercing social insight that most travel guides can only hint at.

(All images and movie posters from IMDB.com)

Table of Contents

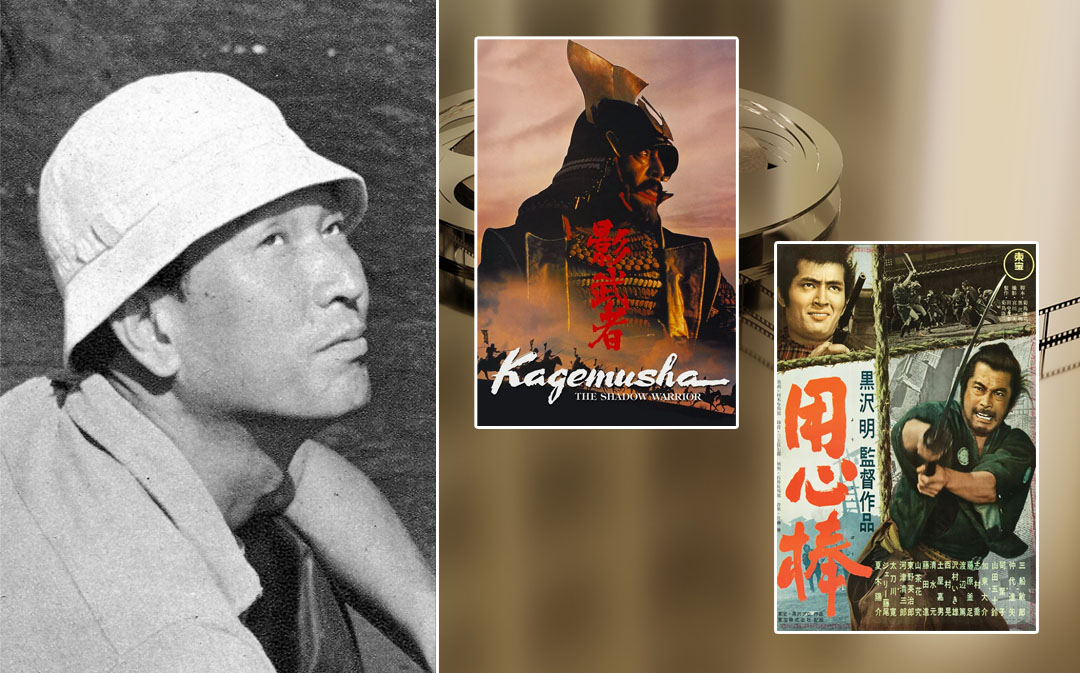

Akira Kurosawa (黒澤 明)

Hands down the most famous Japanese movie director worldwide, and certainly one of the greatest, Akira Kurosawa was the creative tour-de-force that familiarized global audiences with Japanese moviemaking and storytelling styles.

Akira Kurosawa familiarized a whole new generation of movie lovers with medieval Japanese concepts of honor and chivalry.

Renowned for samurai films such as Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, Kurosawa introduced the classic tenets of Japanese honor to worldwide audiences, and in the process, developed a distinctive visual style that incorporated both eastern and western elements. An admirer of classic western works such as Macbeth, several Kurosawa movies were also oriental interpretations of these sagas. A creative direction that further cemented the famed director’s popularity in the west.

In turn, the auteur’s visions influenced numerous other directors and movies; even Star Wars cited Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress as a major inspiration. Following his passing in 1998, Asianweek named Kurosawa as an “Asian of the Century.” For anyone remotely interested in Japanese cinema, his works are the first on any list to watch and enjoy.

Kenji Mizoguchi (溝口 健二)

Renowned internationally for his emphatic, single-scene long shots, Kenji Mizoguchi is widely considered one of the representative masters of Japanese cinema, together with Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu.

Kenji Mizoguchi’s supreme mastery of the mise-en-scène technique is but one reason why he is still regarded as one of the greatest Japanese movie directors ever.

A theatre aficionado and already a recognized name in the era of silent movies, Mizoguchi’s familiarity with the older mediums empowered his later movies with a sophistication that effortlessly “shake and move.” His later films also documented the transition of Japan from a feudalistic society into a modern one, thus cementing their historical importance.

It was during the filming of these later masterpieces, and with the partnership of set designer Hiroshi Mizutani, that Mizoguchi refined his signature “one shot, one scene” method. Simply put, Mizoguchi discarded quick cuts and transitions in favor of extended wide-angle shots. The subtlety of these scenes, and the complementing environment, then delivered a richer story that no dialogue is capable of.

As for specific titles, Mizoguchi’s most famous movie is undoubtedly Ugetsu, a periodic romantic fantasy that is widely regarded as an icon of Japan’s golden era of film. Other notable works include The Life of Oharu, The Crucified Lovers, and Sansho the Bailiff. Many of his earlier works, despite being in black and white, are naturally worth watching too.

Read also:

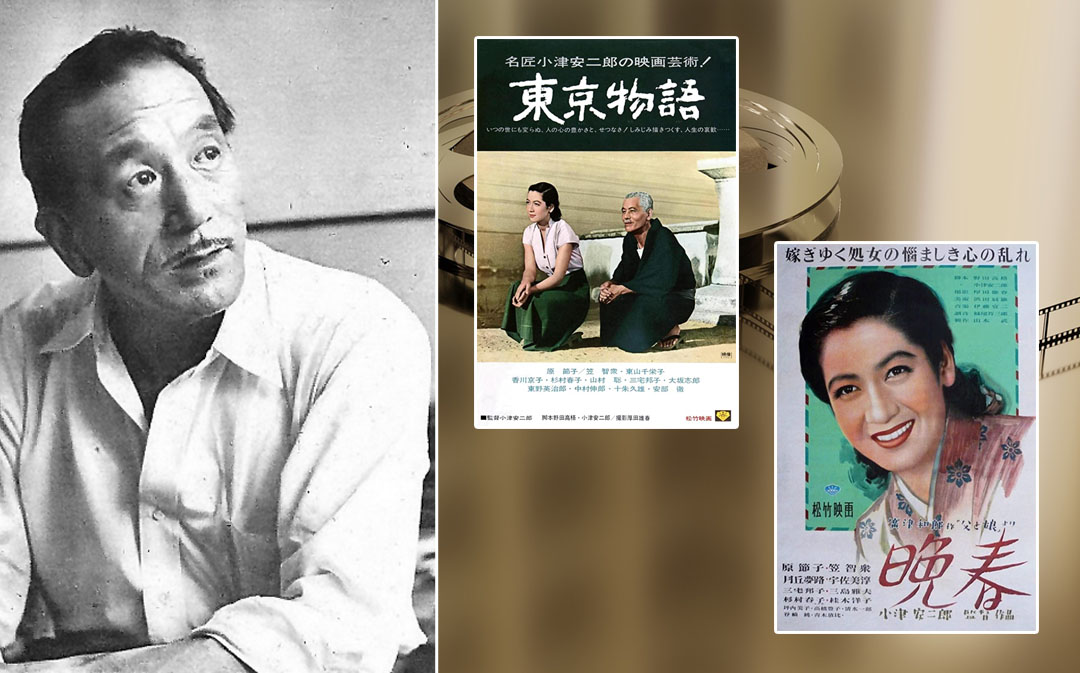

Yasujiro Ozu (小津 安二郎)

Similar to Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu was already an established name during the era of silent movies. Upon transitioning into the modern era, he likewise developed a signature style that’s still celebrated as a milestone in Asian moviemaking.

Yasujiro Ozu’s established many distinctive storytelling and camera techniques. Like Kurosawa and Mizoguchi, he is also hailed as one of the fathers of Japanese cinema.

Specifically, Ozu is famous for his stories on marriage and inter-generation conflicts. But more so, he is renowned for his distinctive visual techniques. Techniques such as extremely low shots, an abundance of static scenes, and actors speaking to the camera instead of to one another during conversations.

Ozu’s movies are furthermore unusual in that they often reject traditional narrative structures. Technically known as Ellipsis, his stories eschew the actual showing of key events and only reference them in dialogue, objects, etc.

If the above adds up to give the impression of inaccessibility, be assured that the master’s films are always immersive, affecting experiences that succinctly communicate complex concerns and themes. His later films such as Tokyo Story, An Autumn Afternoon, and Floating Weeds, are the most splendid examples of this.

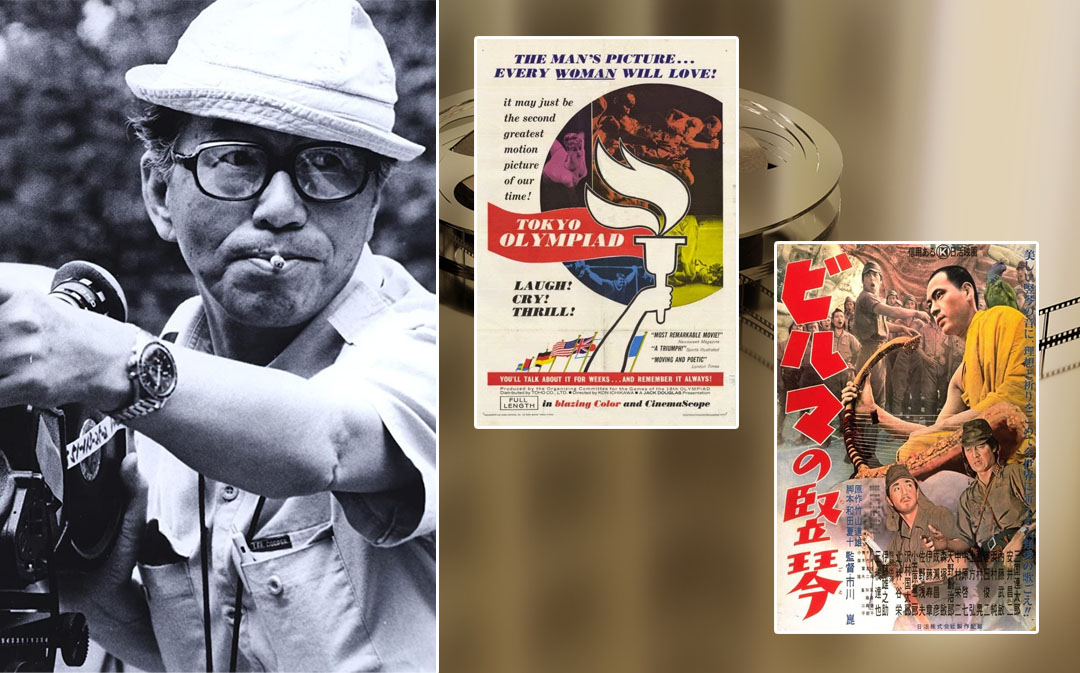

Kon Ichikawa (市川 崑)

Ise-born Kon Ichikawa had a tough younger life. At the age of four, his father died and he was sent to live with his sister. A great fan of drawing and Disney works, he began his career as an animator but was forced to crossover to film when the studio he worked for shuttered its animation department.

Kon Ichikawa was notably anti-war. He also exhibited an enduring versatility with his varied portfolio of works.

He did, however, find renewed inspiration in his wife Natto Wada, a translator, scriptwriter, and film columnist. Together, the couple produced Ichikawa’s most significant works, the most culturally iconic being 1965’s Tokyo Olympiad, a semi-documentary that detailed the humanistic side of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

Other notable Ichikawa masterpieces include The Burmese Harp and Fires on the Plain, both stirringly poignant yet tender expositions on humanity during wartime. As a show of Ichikawa’s professional versatility, he has also worked on science fiction, periodic, and even folkloric works. An example of the latter is the financially successful and elegant Princess from the Moon.

Nagisa Oshima (大島 渚)

While he has directed over 20 movies, Nagisa Oshima is most famous for two productions. In the early 80s, he achieved international acclaim with Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, an intricate WWII prisoner of war tale starring the late David Bowie and Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Nagisa Oshima’s works range from shocking to bizarre, to politically brilliant.

Before Lawrence, Oshima also directed the shocking In the Realm of the Senses. To say this “erotic art” film is one of the most sexually explicit, and gory, movies ever made is a gross understatement.

Apart from the above two, Oshima directed the outrageous Max, Mon Amour too, which features a chimpanzee in a relationship best left undescribed. All these, without surprise, might encourage to consider Oshima as an exploitation movie director in and out. One who only found momentary acclaim with Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

The truth is, Oshima’s long career saw him repeatedly dissect thorny issues such as xenophobia and political disillusion. Some critics have also interpreted the sexual deviances showcased in the director’s explicit productions as platforms for the discussion of such issues.

Technically, Oshima’s experiments with different cinematographic styles firmly establishes him as a leading name in the Japanese New Wave moviemaking era too. For his fans, he is assuredly one of the most daring directors too.

On a side note, don’t be put off by the description for Senses above. This movie is so explicit, it desensitizes. In a way, that is an effective metaphor for the obsessions at the heart of the show. And proof that Oshima deserves a place in any greatest Japanese movie directors list.

Read also:

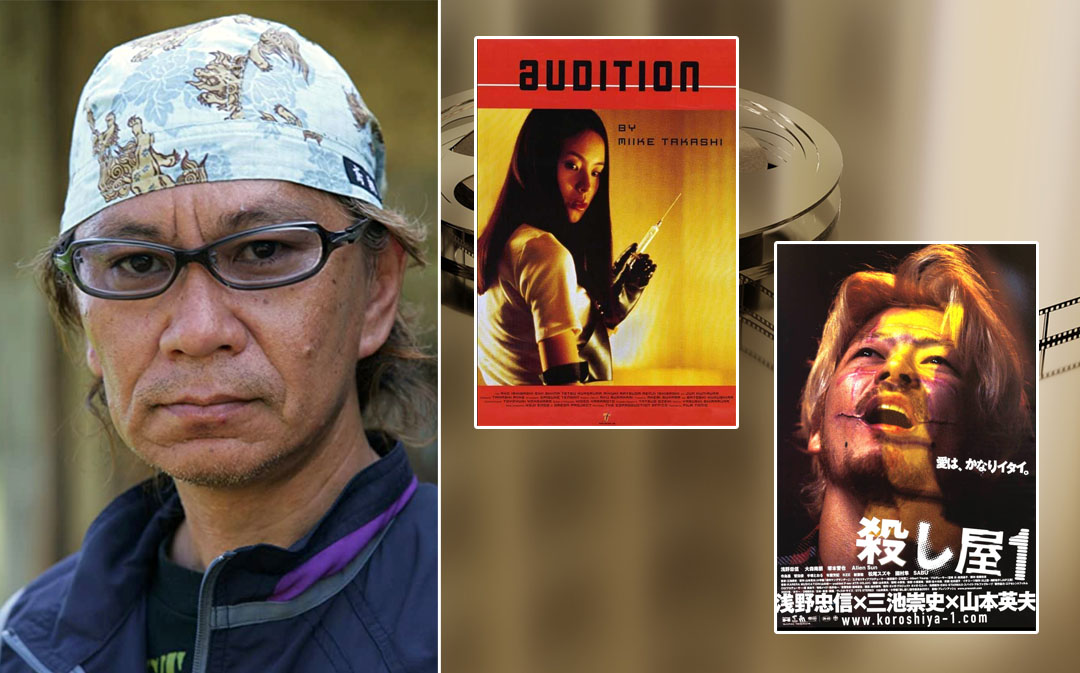

Takashi Miike (三池 崇史)

Some film publications are fond of referring to Takashi Miike as the “bad boy” of Japanese cinema. As true as this is, it is unfair to consider that epithet the only definition of this controversial director. Actually, it’s tough to even classify him under any movie genre.

The bad boy of Japanese cinema has directed over a hundred movies and television series, and is notorious for his over-the-top treatment of violence.

One of the most prolific directors in history, Miike has directed over a hundred movies and TV series since 1991, with productions ranging from the ultraviolent to the horrific, to the downright bizarre. While heavily associated with the gangland and horror genres in the West, thanks to cult favorites like Audition and Ichi the Killer, Miike has also directed video game and manga movie adaptations. For example, Ace Attorney, Like a Dragon, and JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond Is Unbreakable Chapter I.

There are also his surreal titles, the most famous of which is the dark comedy Visitor Q. In short, this is one movie you’d either love or condemn as conspicuously inexplicable.

In view of all, perhaps the only way to define this notorious director is to use the word “audacious.” Not only does Miike constantly challenges censorship boundaries with over-the-top gore and violence, he hesitates not to discuss taboo topics like sexual deviance and xenophobia.

This is one Japanese director whose body of works will surely provide enough material to fill up an academic course.

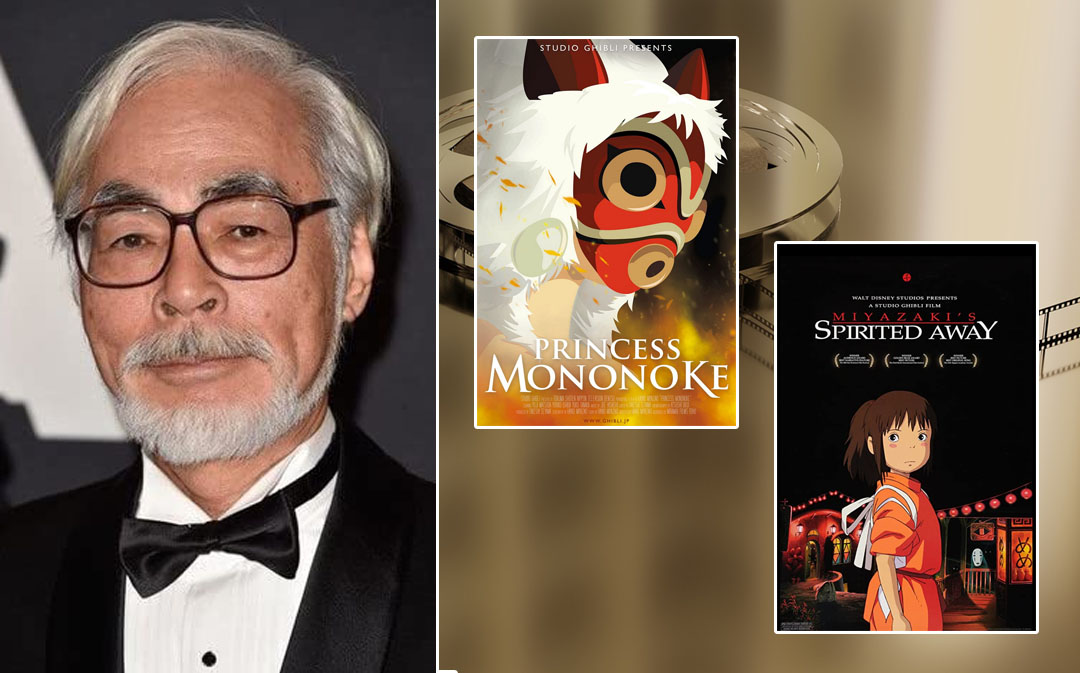

Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿)

In a nutshell, while Hayao Miyazaki isn’t the reason for the current popularity of Japanese animation, he was the one who elevated Anime into a recognized art form worldwide.

The number of tourists enthusiastically visiting Tokyo’s Studio Ghibli Park today is the greatest testament of Hayao Miyazaki’s worldwide success.

Through legendary productions such as My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, and Spirited Away, the Tokyo-born director explored a variety of modern concerns such as environmentalism and feminism. An outspoken supporter of pacifism, Miyazaki’s whimsical and lush films are also noted for never pitting a protagonist against a hardened villain. Most if not all of his antagonists exhibit redeeming qualities.

Thanks to his frequent creative partner Joe Hisaishi, Miyazaki’s movies are additionally renowned for their music. The soundtracks from his most popular works are all considered standard repertoire for Japanese music students.

In short, it is not at all an exaggeration to say Hayao Miyazaki will go down in history as one of the most successful animated filmmakers and greatest Japanese movie directors ever. His cinematic legacy will also continue to shine, and influence later generations, for a long time.

Takeshi Kitano (北野 武)

Simply put, “Beat” Takeshi is a chameleon.

Takeshi Kitano is a comedian, an actor, and one of Japan’s best movie directors. In recent years, he has also done voiceover work for video games too.

Outside of Japan, he is renowned for his numerous acting roles. Within Japan, he is a successful comedian and game show host. The raucous albeit imaginative Takeshi’s Castle in the 80s was his showpiece. In his younger days, his audacious jokes as one half of the Two Beat duo also earned him his nickname and permanent recognition on television.

There are also his directorial works, the most famous of which is arguably the samurai/gangland hybrid Zatōichi. Stylistic, unapologetic with violence, and heavily inspired by Kitano’s real-life interactions with actual Yakuza members, many of his other movies are similar roller coaster rides. Doubly memorable for their sentimental touches and unpredictable inclusion of absurdist elements.

As for those that aren’t, such as the heartwarming Kikujiro, you can expect tender depictions of mankind’s better side. Kikujiro itself was noted for its contrast of Japan’s mainstream lifestyles with those on the fringes too. This is a clear indication of Takeshi’s wide-ranging capabilities.

Yōjirō Takita (滝田 洋二郎)

Yōjirō Takita’s most renowned work is, of course, 2006’s Departures, which won the Best Foreign Language Film Award in the 81st Academy Awards. An insightful glimpse into the Japanese mortician profession, the tender movie was celebrated for its exploration of traditional Japanese taboos and prejudices associated with death. Importantly, Departures was also the first Japanese movie to win an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. This is an accolade that not even Akira Kurosawa could lay claim too.

Before the Oscar-winning Departures, Yōjirō Takita directed two supernatural hits, and a series of movies best left unmentioned.

Since 2006, though, Takita has not released any international hits, which might lead some viewers to consider him as a one-hit-wonder. The truth, on the other hand, is way more colorful. While Takita has only directed four films since winning an Oscar, his cinematic resume is as disparate as any could be.

Before Departures, Takita directed Onmyōji I and II, two glitzy and entertaining supernatural flicks based on the legendary occultist Abe no Seimei. His 2002 Shinsengumi historical drama, When the Last Sword Is Drawn, was also nominated for eight Japanese academy awards, ultimately winning three. (Best film included)

And before these, the Toyama-born director directed a long list of popular “Pink Films.” Such films, best described as Japanese sexploitation movies that are as rude as they are comedic, as they are outrageous.

As far as versatility is concerned, this is one Japanese director who is way up there. This is also a master whose artistic visions can effortlessly move you in a multitude of ways.

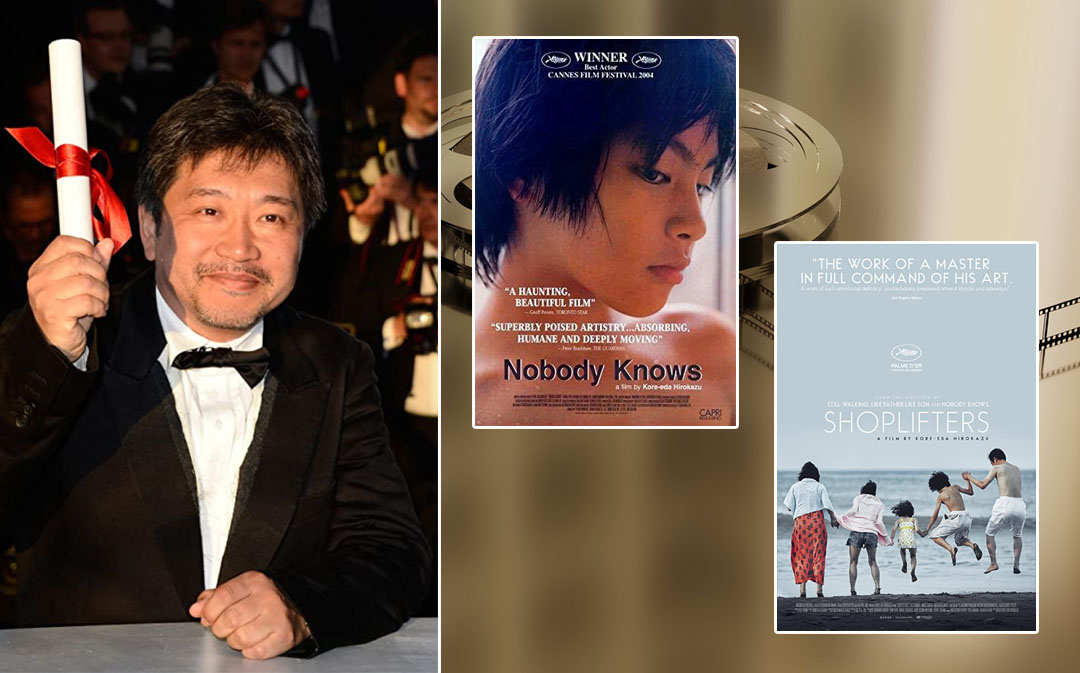

Hirokazu Kore-eda (是枝 裕和)

The current darling of Japanese cinema, Hirokazu Kore-eda is the director of 2018’s Shoplifters. As is well-known, this stoic examination of a dysfunctional pseudo-family in Japan was a huge hit internationally. It also won both the Academy Award and the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s movies are incredibly sentimental and relatable, despite the thorny social issues they explore.

Shoplifters’ quietly affecting, contemplative style is present in many earlier Kore-eda movies as well; a lot of which, incidentally, have enjoyed international acclaim as well. Particularly worthy of mention here is 2013’s Like Father, Like Son. In the same mien as Shoplifters, this poignant drama of a really awful hospital mix-up investigates the question of, what constitutes parental bond? Is it bloodline or shared memories?

And then there’s the disturbing Nobody Knows, based on a true story of Tokyo kids left to fend for their own. A tale simultaneously shocking, gripping, but heartwarming.

Lastly, for something less intense, there is the 2015 production, Our Little Sister. A serenely beautiful take of three sisters welcoming a stepsister into their home, this Cannes Film Festival entry is suitably humorous and introspective at the same time, and with lovely scenery of Kamakura to boot. On the latter, to be able to watch the movie in Kamakura itself is assuredly a travel joy.

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Pinterest for more fun stuff!

Ced Yong

A devoted solo traveler from Singapore who has loved Japan since young. His first visits to the country were all because of video game and Manga homages. Today, he still visits for the same reasons, in addition to enjoying Japan’s culture, history, and hot springs.