The Japanese language is actually quite an easy language to learn. There are none of the gender nouns present in many other languages, and unlike the complicated verb changes of the English language, the Japanese verb tenses generally follow a very regular format. If you’re happy with verbal communication, then it should take you no more than a year to become fairly adept at the language. However, reading and writing are a completely different matter.

Just like in any other language, speaking is much easier since one doesn’t have to deal with most potential grammar specifics. For instance, if you’re a foreign student who arrives at a university, it can be hard to write essays and papers at the beginning. In such instances, students often send a ‘write an essay for me‘ request to a writing service. The thing is, it takes much more time for them to write an essay, and some deadlines can be tight.

The Japanese are well known for their tenacity and attention to detail, and nothing illustrates that more than their writing system. Not content with using the perfectly acceptable Chinese characters, Japan had to add its own original twist on the written language, and is now the proud owner of three different writing systems: kanji, katakana and hiragana. If you must write a more detailed article on this topic at your university, you can always use the essaypro service.

Kanji

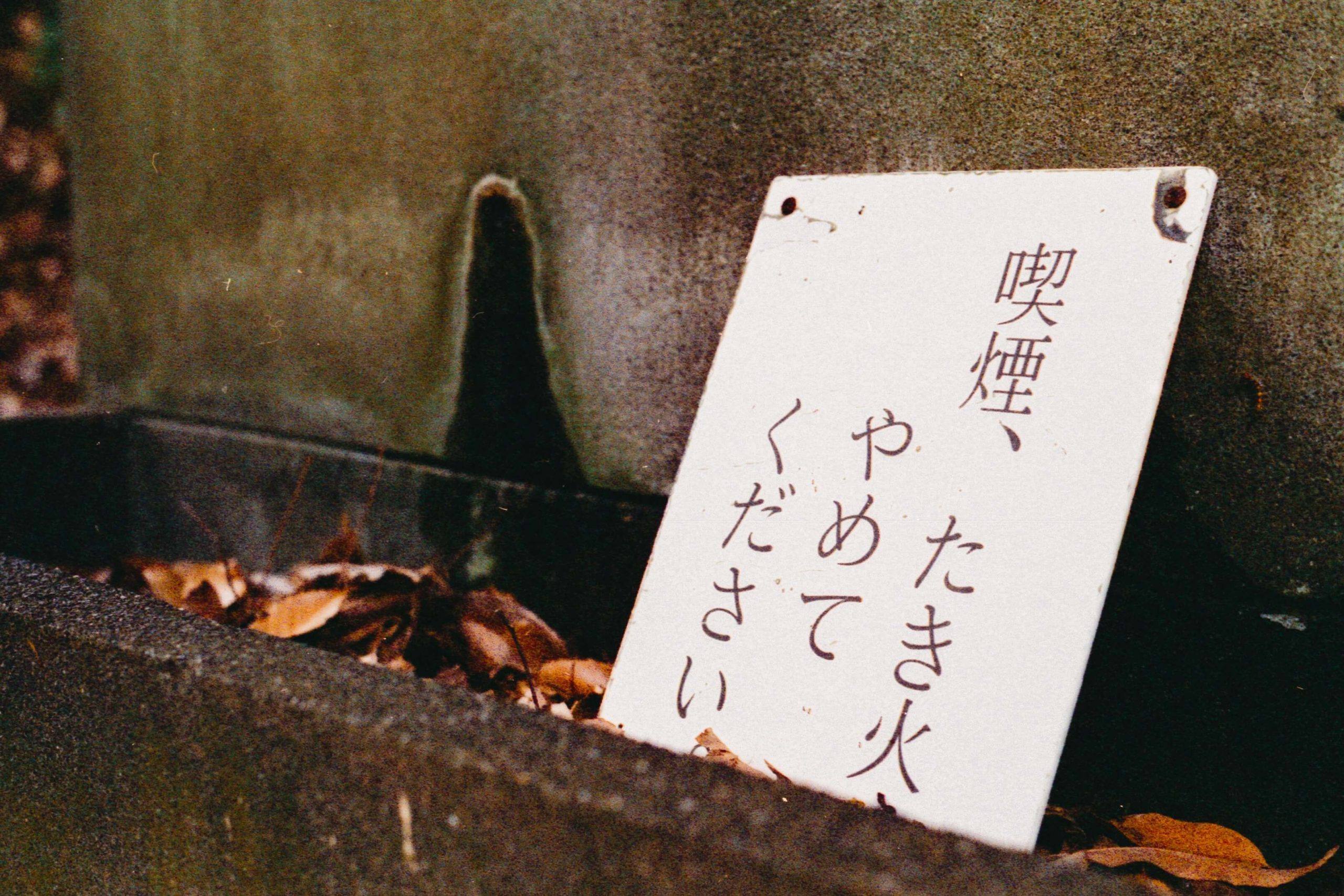

Of the three writing systems, the Chinese character based kanji (written 漢字) is the oldest. It is the earliest writing system in Japan, arriving from China in the 5th century. When the Japanese began to use this new system, they already had a spoken language in place, so the kanji was used in two ways: with the Chinese word (on-yomi), and with the word it represented in Japanese (kun-yomi).

For example, the kanji for “grass” is “草.” It can be read as “kusa,” which is the kun-yomi and comes from the original Japanese, or as “sou,” which is the on-yomi and comes from the Chinese word. Two completely different ways to read the same kanji, but almost every kanji in modern day Japan has both kun-yomi and on-yomi pronunciations.

For example, the kanji for “grass” is “草.” It can be read as “kusa,” which is the kun-yomi and comes from the original Japanese, or as “sou,” which is the on-yomi and comes from the Chinese word. Two completely different ways to read the same kanji, but almost every kanji in modern day Japan has both kun-yomi and on-yomi pronunciations.

So, how do you “read” kanji? Well, the simple answer is, you can’t, and most of early education in Japan is dedicated to memorizing the 2000 or so characters in everyday use. It is possible to guess the reading of unfamiliar kanji by looking for similar traits to others, or from the context, but in most cases, it is almost impossible to decipher without a dictionary.

Hiragana and Katakana

The two other writing systems, however, are much more accessible. Katakana and hiragana were developed by the Japanese in the 9th century, as they began to create their own alphabet distinct from the imported Chinese one. Both katakana and hiragana have 46 characters each and are phonetical, but their purposes are slightly different.

The angular katakana (written カタカナ) was originally created as a shorthand for an ancient style of Chinese, and in modern Japanese is used for loan words, and proper nouns which don’t have a kanji equivalent. Hiragana (written ひらがな), which has a much softer appearance, was derived from the Chinese cursive script. Hiragana differs to the other two writing systems in that it’s not commonly used for words. Its main function is grammatical, giving tense to verbs and adjectives, joining sentences and the like.

The angular katakana (written カタカナ) was originally created as a shorthand for an ancient style of Chinese, and in modern Japanese is used for loan words, and proper nouns which don’t have a kanji equivalent. Hiragana (written ひらがな), which has a much softer appearance, was derived from the Chinese cursive script. Hiragana differs to the other two writing systems in that it’s not commonly used for words. Its main function is grammatical, giving tense to verbs and adjectives, joining sentences and the like.

However, due to the appearance of the lettering, there is a trend in both design and marketing to use hiragana for a word, instead of kanji, to try and convey a different impression or meaning. Compared to kanji, katakana and hiragana are relatively easy to learn. Their alphabets are similar, so while there are 46 in each, learning one will give you enough knowledge to guess the other, and as they are phonetic, anything written with these characters is easily read.

Read also:

So why keep all three?

Kanji is perhaps the biggest obstacle for learners of Japanese. And applies to the Japanese themselves to. In recent years, the increase in phones has meant that fewer and fewer people are writing kanji by hand. Texting in Japanese uses a system where by you type in the hiragana, and choose from a list of appropriate kanji. With less occasions to write, there’s a belief that wile people’s ability to read kanji is unchanged, the ability to write is deteriorating. It’s fairly common to see Japanese people whip out their phone to quickly check the way to write a common kanji.

So if the language is so difficult that even the Japanese struggle, why not change it? This has been a topic of discussion in Japan for many years. So much time and resources are spent on teaching children to read kanji, but in the modern world, where you rarely need to write out anything, and the computer will read it out if you can’t, it’s questionable whether or not this is the best use of the resources available. Wouldn’t it just be easier to use hiragana? Or even better, romaji, where Japanese words are spelled using the English alphabet?

So if the language is so difficult that even the Japanese struggle, why not change it? This has been a topic of discussion in Japan for many years. So much time and resources are spent on teaching children to read kanji, but in the modern world, where you rarely need to write out anything, and the computer will read it out if you can’t, it’s questionable whether or not this is the best use of the resources available. Wouldn’t it just be easier to use hiragana? Or even better, romaji, where Japanese words are spelled using the English alphabet?

Well, no, it would seem not. The writing system has a long history in Japan, it is part of its heritage and culture, and many people are reluctant to give that up for the sake of convenience. Another issue to consider is the different nuances that kanji can convey. Take for example the following two kanji: 想い 思い. Both read “omoi” and both can translate as “to think” but by using the kanji, on the left you can infuse a deeper, more poetic meaning, as in “thinking of you fondly.” Names are also an example of this.

Here, kanji characters are chosen often for their meaning rather than the sound – sometimes to the extent where the way the name is said, has nothing to do with either the on-kumi or kun-yomi. This style of using kanji is known as “ate-ji,” and is common not only for names, but in song writing and other forms of artistic expression. Added to this, there are lots of words in Japanese that have exactly the same pronunciation, but completely different meanings. In general, you can usually understand from the context, but not always, and without the kanji to direct you it can be very confusing.

Read also:

Conclusion – Japanese Writing Systems

So while having three different writing systems may feel unnecessarily complicated to a new learner of Japanese, once you have mastered the language, you realize that there probably is no better way to write it. And, after all, you have to admit, it does look quite beautiful.

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Pinterest for more fun stuff!