Around the cooler months in Japan, you may hear the phrase, dokusho no aki (読書の秋), which translates roughly to “Autumn is for reading”. In Niigata, not only can you experience nature’s breathtaking display of seasonal foliage, but also an impressive selection of stories from the “Father of Modern Children’s Literature”.

Niigata-native Mimei Ogawa has been bestowed the lordly moniker of “The Hans Christian Andersen of Japan”. High praise indeed. Similarly to Mr. Andersen, Mimei Ogawa’s 1,200 original stories, while intended for local children, have grown beyond their hometown and into the hearts of readers everywhere.

The power of the pen

Mimei Ogawa’s beginnings started on April 7, 1882, in the current area of Saiwaicho, Takada City. As if already destined for greatness, Mimei’s father, a staunch admirer of local daimyo Uesugi Kenshin, built the revered Kasugayama Shrine, with some help from his influential friends. Hence, young Mimei’s teenage years were spent wandering and playing around the pastoral Kasugayama area from the impressionable ages of 15 to 20.

In 1901, Mimei Ogawa’s writing career began after meeting his influential teacher, Tsubouchi Shōyō, at Tokyo’s prestigious Waseda University. While a student, Ogawa’s first story, Wandering Child, was published in the pre-war literary magazine New Novel and the experience clearly must’ve lit a fire under his sandals. In 1907, Ogawa’s first collection of short stories, Shujin, hit the shelves. According to a postcard to a friend around this time, we find some encouraging words from Ogawa himself:

“Life should not be a one-way road to improvement, and should not stop after one defeat. “

Mimei Ogawa’s career ran parallel to Japan’s Taisho period, a time where waves of new ideas and movements were flooding the nation. It was this atmosphere, from 1910 to 1928, that Ogawa penned some of his best work and—to our great fortune—gave up on novels to focus entirely on fairy tales.

Required reading

Any reader well-versed in Ogawa’s catalog will tell you without hesitation that his stories rarely end well. The majority of them are either bitter-sweet, or lack any sweetness at all, like your grandfather’s coffee. Nevertheless, the following titles are some of the most endearing:

The Cow Woman (1919): Based among the mountains in his beloved Echigo province, Ogawa paints a crushing ghost story of the love between a deaf and mute woman dressed a black kimono and her prodigal son. Best read with tissues in hand.

The Wild Rose (1920): A heartbreaking chronicle about war wherein two soldiers of opposing armies meet on their prospective borders and witness the beauty of the blossoming roses that grow between them during a brief time of peace. Heavy stuff. A stone monument with text from the story can be found behind Joetsu’s Otemachi Elementary school.

“This is the border far from the capital…. Just at the border, there was a wild rose that no one had planted…”

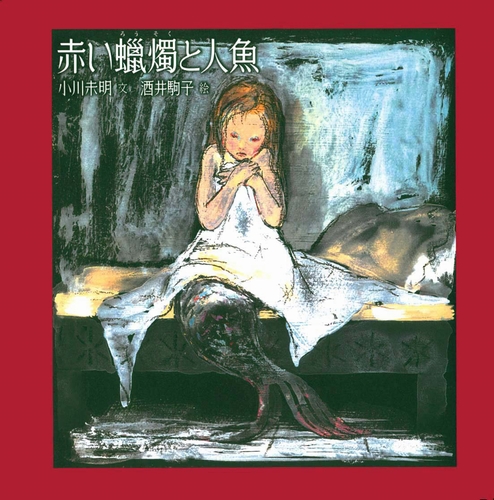

The Mermaid and the Red Candles (1921): A far cry from Disney’s or Andersen’s mermaid, this is a cautionary tale of the dangers of quick monetary gain, and one of Ogawa’s most popular stories. An orphaned mermaid’s exceptional candle-painting skills bring an elderly couple riches, but when a greedy salesman convinces them to sell the poor mermaid, the town quickly falls into ruin. Heavy stuff indeed. I’m not crying…you are.

.

The story continues

Mimei Ogawa carried his ideals into the Showa period and through the upheaval of war. In 1946, he established the Children’s Literature Association, becoming its first president in 1949. However, after World War II, Ogawa’s signature approach of blending humanism and social injustice into his fairy tales came under fire, as they seemed to be too much of a bummer for modern children. Despite the criticism, he never wavered. In fact, it was his stalwart belief that children were just as sensitive as adults to the trials of humanity that transcended his fables from the superficial into the profound.

Those interested in the celebrated author’s catalog can see, read and appreciate his stories at the Ogawa Mimei Museum of Literature, located inside the Takada Library in Joetsu. Or, if museums aren’t really your thing, simply visit the Takada library, check out an Ogawa classic and enjoy it underneath a tree bursting with autumn reds, golds and yellows. Dokusho no aki.

Getting there

Address: Niigata Joetsu-shi Motoshirocho 8-30, Takada Library (Takada Park)

Admission: Free

Josh Furr

Joshua first came to Japan with his family over 10 years ago and it completely ruined his life (in the best of ways). When he’s not trying to pass the JLPT, he’s researching Japanese history, enjoying 80s J-Pop and dreaming of 牛丼. He’s currently writing, writing, writing…mostly about Japan and video games.